This is an advice letter sent to those — like me — who participate in this year’s National Novel Writing month. No, I haven’t gotten anywhere near my goal yet. It’s the holidays! I’m traveling! I have no excuses! But a letter like this one, from Lemony Snicket himself, puts a smile on my face. Lobster and Johannesburg, here I come!

Dear Cohort,

Struggling with your novel? Paralyzed by the fear that it’s nowhere near good enough? Feeling caught in a trap of your own devising? You should probably give up.

For one thing, writing is a dying form. One reads of this every day. Every magazine and newspaper, every hardcover and paperback, every website and most walls near the freeway trumpet the news that nobody reads anymore, and everyone has read these statements and felt their powerful effects. The authors of all those articles and editorials, all those manifestos and essays, all those exclamations and eulogies – what would they say if they knew you were writing something? They would urge you, in bold-faced print, to stop.

Clearly, the future is moving us proudly and zippily away from the written word, so writing a novel is actually interfering with the natural progress of modern society. It is old-fashioned and fuddy-duddy, a relic of a time when people took artistic expression seriously and found solace in a good story told well. We are in the process of disentangling ourselves from that kind of peace of mind, so it is rude for you to hinder the world by insisting on adhering to the beloved paradigms of the past. It is like sitting in a gondola, listening to the water carry you across the water, while everyone else is zooming over you in jetpacks, belching smoke into the sky. Stop it, is what the jet-packers would say to you. Stop it this instant, you in that beautiful craft of intricately-carved wood that is giving you such a pleasant journey.

Besides, there are already plenty of novels. There is no need for a new one. One could devote one’s entire life to reading the work of Henry James, for instance, and never touch another novel by any other author, and never be hungry for anything else, the way one could live on nothing but multivitamin tablets and pureed root vegetables and never find oneself craving wild mushroom soup or linguini with clam sauce or a plain roasted chicken with lemon-zested dandelion greens or strong black coffee or a perfectly ripe peach or chips and salsa or caramel ice cream on top of poppyseed cake or smoked salmon with capers or aged goat cheese or a gin gimlet or some other startling item sprung from the imagination of some unknown cook. In fact, think of the world of literature as an enormous meal, and your novel as some small piddling ingredient – the drawn butter, for example, served next to a large, boiled lobster. Who wants that? If it were brought to the table, surely most people would ask that it be removed post-haste.

Even if you insisted on finishing your novel, what for? Novels sit unpublished, or published but unsold, or sold but unread, or read but unreread, lonely on shelves and in drawers and under the legs of wobbly tables. They are like seashells on the beach. Not enough people marvel over them. They pick them up and put them down. Even your friends and associates will never appreciate your novel the way you want them to. In fact, there are likely just a handful of readers out in the world who are perfect for your book, who will take it to heart and feel its mighty ripples throughout their lives, and you will likely never meet them, at least under the proper circumstances. So who cares? Think of that secret favorite book of yours – not the one you tell people you like best, but that book so good that you refuse to share it with people because they’d never understand it. Perhaps it’s not even a whole book, just a tiny portion that you’ll never forget as long as you live. Nobody knows you feel this way about that tiny portion of literature, so what does it matter? The author of that small bright thing, that treasured whisper deep in your heart, never should have bothered.

Of course, it may well be that you are writing not for some perfect reader someplace, but for yourself, and that is the biggest folly of them all, because it will not work. You will not be happy all of the time. Unlike most things that most people make, your novel will not be perfect. It may well be considerably less than one-fourth perfect, and this will frustrate you and sadden you. This is why you should stop. Most people are not writing novels which is why there is so little frustration and sadness in the world, particularly as we zoom on past the novel in our smoky jet packs soon to be equipped with pureed food. The next time you find yourself in a group of people, stop and think to yourself, probably no one here is writing a novel. This is why everyone is so content, here at this bus stop or in line at the supermarket or standing around this baggage carousel or sitting around in this doctor’s waiting room or in seventh grade or in Johannesburg. Give up your novel, and join the crowd. Think of all the things you could do with your time instead of participating in a noble and storied art form. There are things in your cupboards that likely need to be moved around.

In short, quit. Writing a novel is a tiny candle in a dark, swirling world. It brings light and warmth and hope to the lucky few who, against insufferable odds and despite a juggernaut of irritations, find themselves in the right place to hold it. Blow it out, so our eyes will not be drawn to its power. Extinguish it so we can get some sleep. I plan to quit writing novels myself, sometime in the next hundred years.

–Lemony Snicket

Lemony Snicket is the author of A Series of Unfortunate Events. You can learn more about his work here.

Filed under: Advice, Books, Writing | Tagged: fiction, Lemony Snicket, NaNoWriMo, novels, Writing | 2 Comments »

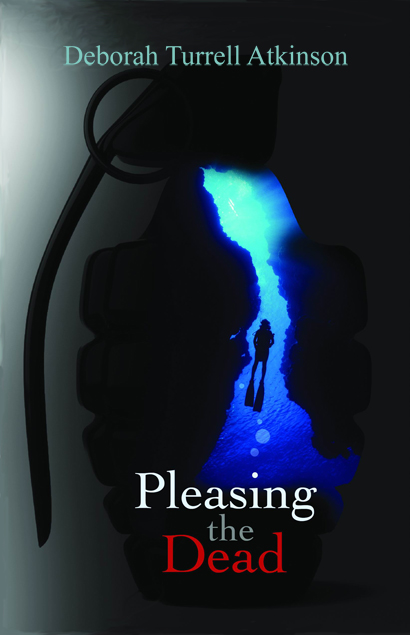

ils from Honolulu and writes atmospheric mysteries set in Hawaii. But not from the tourist point-of-view so you really get a feel for what it must be like to live and work in the Islands. Her new book is Pleasing the Dead, from Poisoned Pen Press.

ils from Honolulu and writes atmospheric mysteries set in Hawaii. But not from the tourist point-of-view so you really get a feel for what it must be like to live and work in the Islands. Her new book is Pleasing the Dead, from Poisoned Pen Press.